One important skill for a chess player is to feel the moment in a game when you really have to think hard and an make an important decision or two. How well do you sense such critical situations? In analysis, you or your engine can always identify the blunders, when advantage switches from one side to the other. But what about during the game? To measure your skill – I suggest recording time spent on each move on a score sheet during the game. While going through the game afterwards – it will be not hard to tell whether you spent enough time during the critical moments. You can also improve your time management by identifying moves on which you spent more time than necessary!

Looking at time spent will also reveal what of opponent’s moves came to you as a surprise…

Here is an example played with 1 hr 30 minutes per game, and 1 minute increments:

Yoos - Jiganchine, Keres Memorial 2009.

1. e4 c6

2. d4 d5

3. e5 c5

4. dxc5 e6

5. Be3 Nd7

6. Nf3 (1-24) Qc7 (1-29)

7. c4 (1-19) dxc4 (1-12)

8. Qa4 Bxc5 (1-11)

9. Bxc5 Qxc5

10. Nc3 Nh6 (59)

11. Ne4 (1-12) Qc6 (49)

Without even looking at the board or replaying the moves, this time spent after moves tells a story! Looking at the moves again, what can we see?

1. e4 c6

2. d4 d5

3. e5 c5

4. dxc5 e6

5. Be3 Nd7

The main line now is 6. Bb5

6. Nf3 (1-24)

Jack was spending several minutes here, so I was already feeling that my opening choice was not completely bad. But was he trying to remember theory, or just choosing which line to play to surprise me the most? He in fact had already played Nf3 in one of his games before!

6 ….Qc7 (1-29)

Now, the usual move is 6… Bc5, but because Black plays 6… Qc7 against 6.Bb5, I played the same move without much thinking. Clearly I did not sense an important difference between 6. Nf3 and 6. Bb5

7. c4 (1-19)

White must have either had this prepared at home and he was double checking, or it was part of his plan with Nf3. Either way, he was not spending too much time here yet.

7… dxc4 (1-12)

The almost 20 move think on move 7 shows that clearly I had not expected 7.c4, even though this is a somewhat common idea, and makes more sense with the queen on c7, rather than on d8.

8. Qa4 Bxc5 (1-11)

Only reasonable move, so makes sense to play it fast.

9. Bxc5 Qxc5

10. Nc3

Now Black has to choose between Nh6 and Ne7, so here comes a 10 minute think.

10… Nh6 (59)

11. Ne4 (1-12)

Again, White is playing reasonably fast, and at this point Black has to choose between 11… Qc6 and 11… b5 !?

11… Qc6 (49)

11 moves into it, I I already spent almost half of my time. I carried on in a similar fashion, got into time trouble and made a decisive blunder on move 16 already. All that could have arguably been prevented had a put a bit more thought on my critical decision on move 6, which I clearly did not!

David Bronstein had also been advocating including time spent as part of the game scores – since it is just as much part of the game as the actual moves! You can learn more about the trends in you play - going through the records of my games I noticed that in most games that I have lost – I had been spending more time than my opponent starting from the opening – this game against Yoos is a typical example.

It is a good tool for evaluating your overall understanding of the game as well. Mark Dvoretsky has an example in one of his books where he played an anti-positional move and immediately realized its flaws. He then goes on to explain that the fact that he played it very fast means to the coach that he is impulsive, whereas if he had spent a long time on it – that would have revealed poor positional understanding.

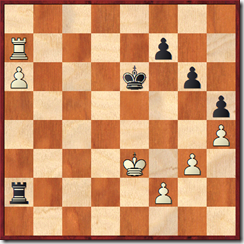

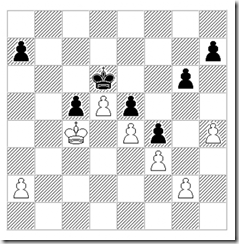

![[image%255B5%255D.png]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjpjBGaoQwFX7Ko_lkt3nBlHXwR4NNLm_9Vf3Te9fFELiyDSZsIQInlHXP-ZujTXRp2pOzt4MDLXhyX0Ui3BqDbdVvRYXv5lm3ipLsytGYlQopqmRrpVyWgGuaHHgFIcuiWzozp10-1mkzl/s1600/image%25255B5%25255D.png) I wrote about the diagram: “This type of positions is considered to be a theoretical draw because the Black rook is behind the ‘a’ pawn.” Well, I forgot about the entire chapter on this type of positions that I had read in Mark Dvoretsky’s “

I wrote about the diagram: “This type of positions is considered to be a theoretical draw because the Black rook is behind the ‘a’ pawn.” Well, I forgot about the entire chapter on this type of positions that I had read in Mark Dvoretsky’s “