And incidentally, in all 3 games I played the Caro-Kann defence. Anyway, around the year 2000, I wrote an article about rook endgames, one of the examples was the Charbonneau game from below, and another was the famous Tarrasch – Rubinstein. Collecting and analysing a dozen instructive positions obviously did not prevent me from making mistakes in my own games, so here is further proof. Try to figure them out yourself first. They are not trivial, but given that you only have 2 reasonable choices, there is always a good chance of getting it right.

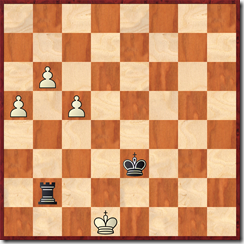

Game 1: Charbonneau – Jiganchine, CYCC 2000, Edmonton

Game 2: Krnan-Jiganchine, Canadian Championship 2004, Toronto

Should the Black king support the ‘c’ pawn (e.g. Kc7), or instead rush to stop the ‘h’ pawn (e.g. Ke7) ?

Game 3: Kostin – Jiganchine, Keres Memorial 2006, Vancouver

In the game White blundered, but I returned the favour and missed my chance for a draw, which was quite instructive.

We learn from our mistakes as more than from our wins, that’s maybe why I still remember these 3 games (ok, having them in a database helps too). Each one of these 3 positions required a bit of calculation, bit of planning/visualizing, and a bit of precise endgame theory knowledge. The second game (against Krnan) was particularly upsetting because after defending for a long time, I actually hoped to make a draw, whereas in the other two games I kind of expected that I might likely lose.

PS. I finally figured out how to make the volume louder in my videos - by using ffmpeg, not by yelling into my dysfunctional microphone. For me that’s probably the biggest win out of studying these 3 endgames.

No comments:

Post a Comment