During Canadian Chess Championship in 2002, I had a pretty odd incident related to memorizing opening variations. In round 4 game I forgot my preparation literally on the next move after we entered the line I had prepared. I lost that game without putting up much resistance. In round 8 game, however, I without any particular effort played to 33rd move from my opening preparation and got a winning position, later managing to convert my advantage. How could this have possibly happened to the same player, in the same tournament?

In reality both examples had little to do with my memory being bad on one day, and good on another, but rather with how familiar I was with the ideas of each line. The line I chose in round 4 was prepared for that particular game; it was a suspicious sideline, and Black had to play carefully after violating some basic opening principles. Round 8, on the other hand, followed a line that I had played a lot with both colours in the past, and before the game I simply refreshed my memory and looked up the particulars. That being said, my round 8 opponent had also been well familiar with that line; he lost partially because he had been anticipating me to play other lines, and did not refresh this particular variation in his mind before our game. Below are the actual examples.

Glinert – Jiganchine, Richmond, 2002, Round 4 (Replay the game in the viewer, or watch a youtube video with full analysis)

In the Panov attack, Black ventured with a very rare Qa8 and Rd8, to which White responded in a logical way with Bd2 and Ne5. I had planned to play along Krogius,N-Kortchnoi,V/Tbilisi 1966 where Kortchnoi continued with 12… Nf6, defending his kingside, and opening up the d file. I had been looking at that game several hours before the clocks were started! Instead I played 12… Nxe5?!, and lost because of difficulties getting Bc8 into the game.

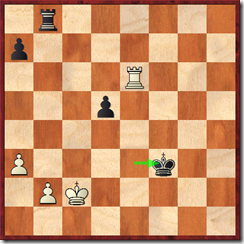

Jiganchine – Sokourinski, Richmond 2002, Round 8 (Replay the fully annotated game)

We are in the end of a somewhat forced opening/endgame variation – also in the Panov attack. Black had just finally regained a pawn with 32… Kxf3?!, but the cost is too high: his king is cut-off, and White threatens to transfer the king to d4. With the prepared (just before the game) 33. b4! White frees up the king from guarding b2, and has excellent chances to win the game.

I’d also summarize as to main reasons I think chess players have a hard time forgetting their chess openings (I am sure you can think up a few more)

- Not familiarizing themselves with ideas, but rather trying to remember individual moves – that just never works, at least not for me!

- Getting confused by move orders. You can even remember the ideas, but playing them in a wrong order is pretty common

- Confusing similar variations. Often I remember that a particular move has to be played, but it actually applies to a different position with similar characteristics

- A non-forced nature of the opening. Glinert-Jiganchine is a concrete position, but the threats have not materialized just yet.

- Broad variety of options. In Jiganchine-Sokourinski, we got to move 33 by grabbing each other’s pawns and pieces pretty much non-stop along a narrow path. It is way harder to remember the correct path when the lines branch off in various directions